Return from Kibuye

After Kibuye, we had planned to visit a memorial called Bisesero where genocide victims successfully resisted the killings for days by gathering in large numbers on the top of a hill and hurling stones at attackers. They succumbed to the violence when military forces from the government at the time reinforced the Interhamwe and launched a large-scale attack with sophisticated weapons.

However, we returned to Kigali instead because a friend had set up a meeting for us with someone who they said was interested in funding a film about a survivor in Butare (southern Rwanda). That meeting was with Esther Mujawayo, who helped start an organization called Avega that offers a support network for victims of genocide. She began the initiative in 1994 with several other women in her community who had lost husbands and family members to the genocide, and started by simply joining together and talking about their experiences. She told us that there is no way she could have made it through the trauma without that support. Now the organization has over 25,000 members and offers services in both physical and psychological support.

That night, we went to a film screening that included the Rwandan premier of "Shake Hands with the Devil," based on the book by Romeo Dallaire who was the Force Commander for UNAMIR, the UN's peacekeeping mission in Rwanda during the genocide. This film was directed by Roger Spottiswoode, who has also directed notable films such as the James Bond "Tomorrow Never Dies" and the poignant "And the Band Played On." He introduced the film himself and I realized we had met him before when we were filming and photographing a play at a youth center and he had asked to use my monopod for his camera. Good thing we were friendly to him that day! After the film, we joined him for drinks and had very interesting conversations about American culture, international involvement and inaction in the genocide, and thoughts about filming a documentary in Rwanda today. He is actually pursuing a similar project to "A Truth Untold" looking at reconciliation and the 15th commemoration. The following day, he graciously agreed to do an interview in which he discussed some key topics to our film and an important perspective on the international community's role in commemoration and the owning of our actions. We are hoping to post that interview to the site soon, along with other interviews mentioned in this post.

On to Congo

After interviewing Roger, we got on a bus to the border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and spent the night in the Rwandan town of Cyangugu because the border closed before we arrived. We were traveling to Bukavu, DRC to visit a friend I had met on a bus several months ago who will remain nameless for now to protect his privacy. The following morning, he met us in Cyangugu and we made the short, but beautiful journey into DRC along the shores of Lake Kivu. In Bukavu, we explored the city and spent time with my friend, his brother, and members of his family including a police chief, whose young son had never talked to a white person before. We noticed many interesting things on our walk through the city, including the absurd amount of UN offices and vehicles, which seemed to be doing nothing at all except offering employment for foreign militaries. We also got to experience firsthand the reverence given to the flag in a police state like DRC. As we were walking through a busy section of town, we heard a whistle blow and time seemed to stand still. Every engine stopped running, all conversation halted, and no one moved a muscle as they stared at the flag that was being pulled down the mast. When it was removed, the whistle blew again and the hubbub continued immediately as if it had never stopped in the first place, almost as if someone were hitting pause and play on a remote control.

The most interesting part of this trip for me though was conversations we had over drinks the first night in town. My friend's brother showed us scars on his shoulder and upper arm from a grenade that had been thrown into his secondary school by the Rwandan military. He described the time in 1996 when Rwandan soldiers entered the country at the beginning of the First Congo War. He and many other students at the time organized peaceful protests where they stood in the streets with signs to send a clear message that they did not want Rwandan military presence in their city. The response was to surround his school several days later and throw grenades inside, injuring him and killing many of his friends. These are the same soldiers who advanced into Rwanda to stop the genocide and take back the country, and soldiers of a government trying to fight genocide ideology and violence. This is not necessarily a criticism of this government, only an acknowledgement that these are perspectives we don't often get when living in Rwanda. Both brothers also described a horrific incident that happened that same year when the combined military forces of Mali, Chad, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, and DRC chased Interhamwe from refugee camps in the area into the forests. The brothers described how the Interhamwe loaded their families on buses in a place called Tingi Tingi to appear as if they were taking them into hiding with them, then massacred them in a similar way as they had done with the Tutsis in 1994, only this time using guns and ammunition instead of machetes. This story gave me chills and once again reminded me of the mystical nature of this place which manifests itself profoundly in both beauty and evil.

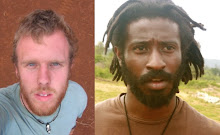

From Bukavu, we took an overnight boat to Goma across the entire length of Lake Kivu, sleeping on the deck in the open air. On the way, we processed and discussed our journey and the stories we were hearing, all the while staring into the darkness of shoreline forests where we knew there were genocide perpetrators hiding and possibly even watching our boat cruise by. When morning broke over Goma we met our friend Olivier, a Rwandan filmmaker and journalist who agreed to show us around Goma and his original hometown of Gisenyi where he had not returned for 13 years. Olivier spent much of his childhood in Goma and explained how he never mentioned his Rwandan heritage for fear of violence and discrimination, explaining that when you are living in a country in this part of the world, you claim that nationality for that time. Our first stop in Goma was a refugee camp called "Centre Chretienne du Lac Kivu" or CCLK. There are 6,039 people living in self-constructed house structures in this camp, and yet they are not officially recognized by the United Nations, so they do not even receive the meager yet consistent rations provided by UNHCR. We began our visit in a makeshift tent ironically constructed of sticks and UNHCR burlap bags that had been presumably scavenged from the little aid they do receive. In this tent, we met and talked with the president and several other members of the camp's governing council. Everyone who spoke was adamant about our obligation to tell the story to the outside world and pleaded to send our footage, images, and stories to CNN, BBC, and any other large media outlet who may listen. We proceeded to tour the camp and were invited inside one of the dwellings, whose two chambers were no bigger than the tent I used to take camping as child, yet housed five people consistently and included an area for cooking. The word used most often by those we met was "nightmare" and I got a sense of desperation in highlighting the incredible challenges they were facing in the remote hope that someone would actually come and help them improve their lives. In the midst of all this, I found resilience in the incredible stories of raising multiple children in this environment and to continue living against all odds. But ultimately, I left feeling completely powerless as I contemplated what it would take to mobilize significant action on this issue, especially considering all the other work we are doing for this project and the general political disinterest, especially given the current financial crisis. For now, all I can do is tell the story and hope it reaches the right people. I plan to post videos from this experience as soon as I have a few hours to gather the footage and the internet access to upload it. Keeping up with the media component of this trip and providing timely updates is a near impossible challenge with the resources we have available, but we hope to continue developing this site for months to come as a historical document.

After CCLK, we toured a facility run by "Heal Africa," whose name bothers me with its generality and presumption, but whose services are important and much needed in this area. Their primary focus is finding rape victims, treating them, and helping them on the road to recovery and healing. Last year, they treated nearly 14,000 patients including a small number of those otherwise injured in war-related activities. Amir received an annual report of their activities, so hopefully we can do a more in-depth post on their work soon.

Back to Rwanda

After taking in all of this in one morning, we crossed back into Rwanda to Gisenyi, where we checked into a low-end guesthouse and departed for the genocide memorial. We were greeeted at the memorial by Innocent Mabamda, who is the president of IBUKA for the Gisenyi sector and the vice-president for the Rubavu district. Innocent had left a memorial service for a Hutu who was killed for harboring Tutsis during the genocide to come see us and show us the site. Gisenyi's memorial site is in a field that is bordered on one side by beautiful towering hills, and another side that leads down to the shores of Lake Kivu. The wall that surrounds the graves was funded and built by the survivors themselves in an order to preserve the memories of what happened 15 years ago. Innocent explained how the Interhamwe had come in several stages to conduct killings and reminded me how terrifying and confusing that situation must have been for those who chose to stay. In the end, Innocent decided to flee across the border to DRC, leaving much of his family behind. His story is a common one in this area and the complete version will be posted to the website soon. Following the tour, we joined him and his wife in their house for some drinks and continued our conversation about each other's home country and culture.

"If someone asks you for forgiveness, you too become free"

The following day, we took motos in the rain to a site at Nyundo, where many people were killed in a church and the surrounding area. Our guides Rose Mukagesagera, Nyirarukundo Annvalite, and Kiwazerifuko Emmanuel explained that many seminary students were killed in these massacres, and that several priests were involved in the killings. One particular priest participated in these murders, then moved on to assist in the bulldozing of a church on top of 3,000 victims who had taken shelter there. Another priest moved to Italy shortly after committing these atrocities and is presumably practicing his order there to this day. He is one of many genocide perpetrators living in multiple countries around the world, several of which knowingly house these murderers such as Agathe Habyarimana in France. But that's a different story.

Two of our guides, Rose and Emmanuel, had been married before the genocide and were both able to escape and find each other later in the hills surrounding Nyundo. As with many survivors, I sensed a purpose to every word they spoke and a subtle acknowledgement from them that they believe they survived for a reason. For now, that reason is to continue to tell the story of what happened, to give that gift of remembrance to those who lost their lives. When asked about forgiving her perpetrators, Rose responded simply: "If someone asks for forgiveness, you too become free."

Ruhengeri

From Gisenyi, we headed to Ruhengeri where we were joined by a Rwandan lawyer who works with IBUKA in Rubavu District and Nyabihu Sector to pursue justice and encourage reconciliation, often in the form of Gacaca community courts in which the community itself tries the offenders. We began our tour of the Ruhengeri memorial site by visiting a courthouse where victims gathered for protection before they were killed in large numbers. At the burial site, a woman survivor told the story of the area and explained that people choose to forgive the killers of their families for several reasons. First and foremost, she explained that the government encouraged forgiveness, so it had become a sort of civil responsibility. She also explained that revenge will not bring anyone back, and that often, survivors have no other choice but to forgive. In our interview with the lawyer, he stated that these things are true, but that no one can forgive someone who has not asked for it in the first place. One problem Rwandans face is that many of the killers still feel no remorse and do not want to be forgiven because they continue to harbor the ideology that led to the massacre in the first place. However, he was hopeful and quick to point out the progress that has already been made, and the unique and powerful examples of reconciliation that we have been privileged to see with our own eyes over the past few weeks.

And Beyond

Tomorrow, we head to Cyangugu accompanied by a Rwandan friend who adamantly insists we join him to get as many compelling and diverse stories as possible. More to come on that soon...

Hello, I like the blog.

ReplyDeleteIt is beautiful.

Sorry not write more, but my English is bad writing.

A hug from Portugal